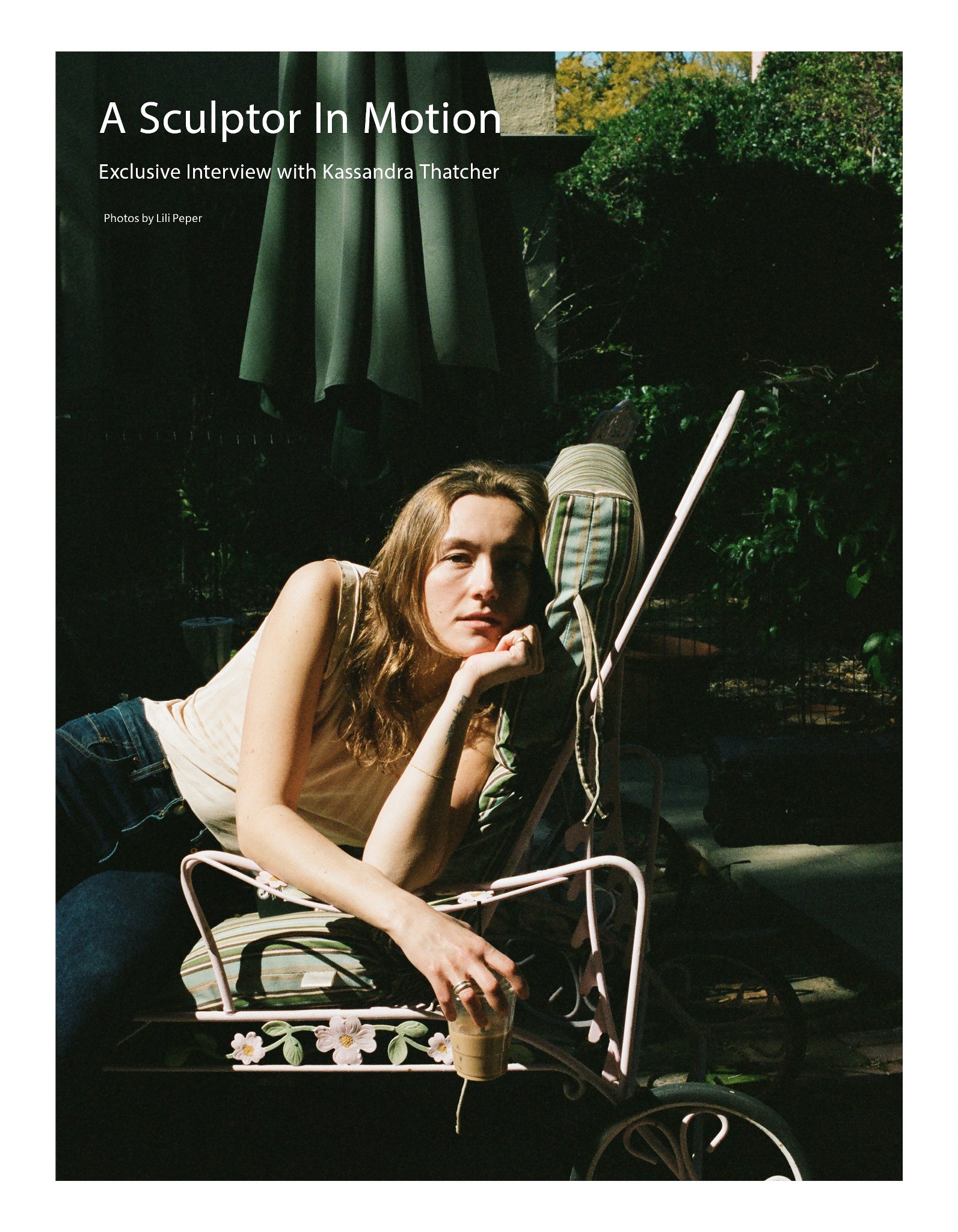

Questions by Sarah-Eve Leduc, Text by Morgan Leet & Photos by Lili Peper

New York born ceramic lighting and sculpture artist Kassandra Thatcher’s work illustrates the human body in motion. Her two collections, Lighting and Sculpture each explore spatial relations and movement, using clay as her primary material.

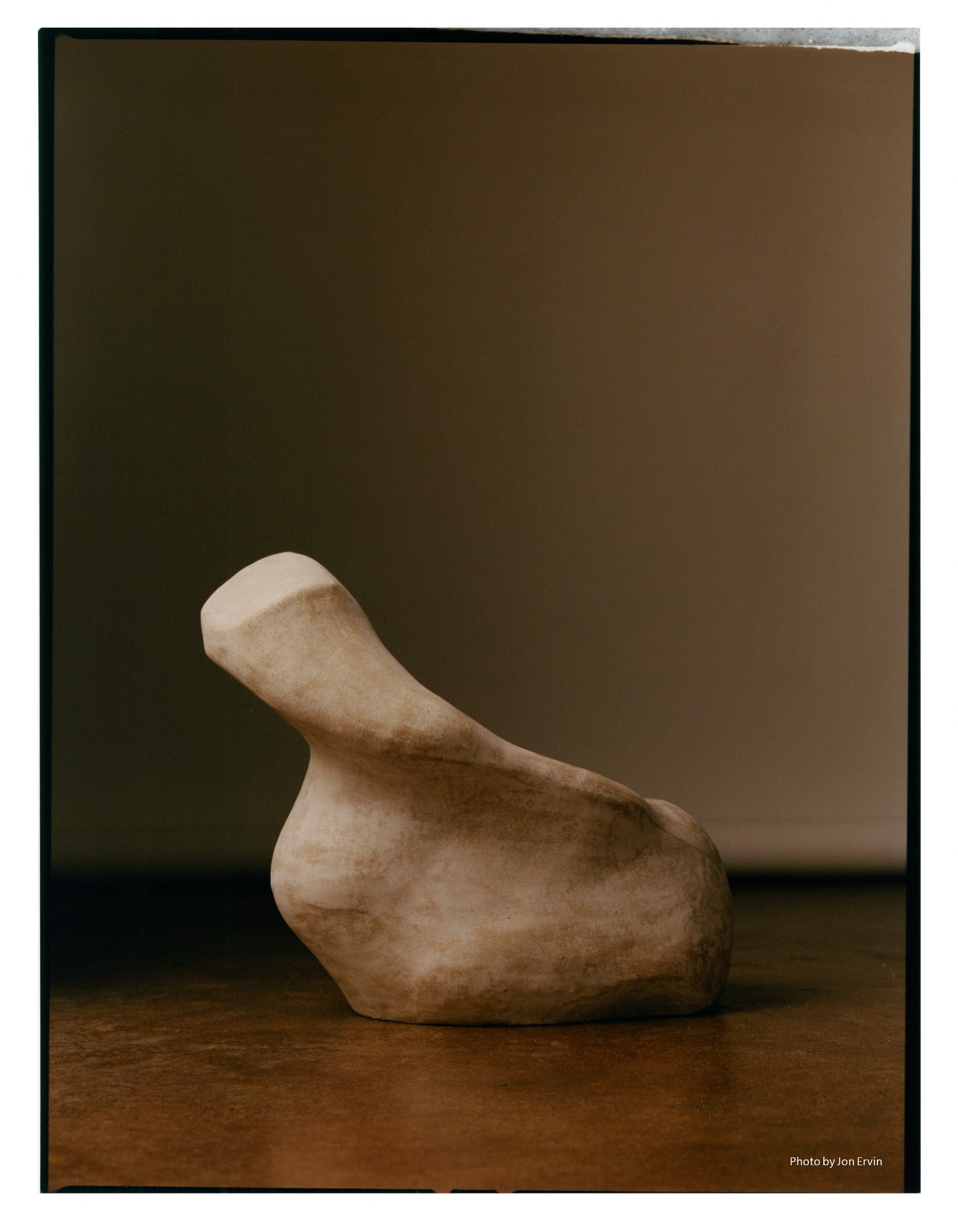

Her Lighting collection merges functionality and art, each sculptural lamp inspiring you to consider the relationship between space, movement, light, and form. The collection is made up of table lamps, floor lamps and sconces. Her Sculpture collection is improvisational, and experiments with the unique contours and gestures of the body.

Her work as a whole encapsulates the movement of the body, each piece capturing the contradiction of stagnancy and motion. Her interpretation of the human form results in fascinating curvatures that captivate onlookers. It’s no surprise that previous to the launch of her sculpting career she was a dancer; her body suspended in motion, similar to that of her work. When viewing her collections this experience is tangible, as the movement of dance is present throughout her art.

Thatcher studied poetry at Bard College before going on to work under the acclaimed artist Stephen Antonson, and then embarking on her own studio in 2018. Her work has quickly gained widespread attention and praise, and she now known for her signature style of the static gesture.

Thatcher spoke to Flanelle to share her story, and perspective on creativity.

Were you a creative child?

I think all children are creative, and that it’s really just a matter of whether or not it was encouraged within your family. For me there wasn’t a question, growing up, of whether or not I would pursue an artistic path — it was expected of me. It was the only option. I was raised in downtown Manhattan in the ‘90s by parents who were graphic designers and were totally immersed in the art scene. I was one of those babies that was fast asleep in the bustling, smoke-filled brasserie. I say that just to give some groundwork for how open and exciting the world seemed from such a young age.

I was signed up for printmaking, ceramics, photography, theater, dance, chorus, and I often struggled to find myself within these practices. There were times when it was too overwhelming and saturated, how much my parents believed I would be an artist. As a child in a household with alcoholism I struggled a lot with expressing myself in the normative world, I was really hard on myself even when so young, and so I was really drawn to the ability to express myself through a medium outside of verbal communication. I spent all my days learning how to speak through art; how to pull my deepest fears out of the depth and convey emotion through performance, through sculpture, or whatever it was.

You studied poetry. What do you find connects art in words versus art in the physical form?

It was necessary to focus on that practice ahead of developing my language with sculpture. Or rather, I think my relationship to my formal practice within sculpture would be in a really different place than it is now if I hadn’t started there. It’s not so much about words versus objects in making art — because in a way there are obvious differences there — but about how language gives you the tools you need to understand how things are brought into being. With words there’s more room for understanding the language of form and how instrumental it is in creating.

My mentor in college, Ann Lauterbach, who is a renowned poet herself, had this beautiful taxonomy of poetry that she came up with and that has been a map for me throughout my work, both when writing poetry and now with sculpting. She details how content is the result of a convergence with form and subject matter, and therefore meaning is a result of these elements in conversation. The work I did in college was focused on the minutiae of everyday experiences, zooming in on the small ordinary occurrences like your senses, through specific formal boundaries. Through that practice, once you go back and read what is written, you see content and meaning emerge from description. So, this is how, in my sculptural work, I landed closer to abstraction and biomorphism. I’m more interested in exploring form by picking a subject or use, and from there allowing content and meaning to arise on its own.

When did you know you wanted to pursue sculpting as a career?

After I graduated college I was sort of floundering, not knowing what I wanted to do and feeling a lot of pressure to know, so I started working in NYC galleries. It was the first time in my life that I didn’t have creative practice as part of my day-to-day. Things were feeling bleak. So, I got a membership at a clay studio and started playing around again. I started making my sculptural work functional because I was really interested in existing in the space between art and design and merging them. I was getting more recognition for the lamps I was making, because at the time there weren’t many people making ceramic lighting, so I felt encouraged to pursue it. I was 23 at the time so I was like “if this doesn’t work, I have time to find something else.” I worked in a restaurant part-time until I could get my bearings with my work because I wanted to make sure the work wasn’t being made just for the sake of making money.

After school, you assisted Stephen Antonson, a renowned plaster artist, on the weekends. What did this bring to your creative process? How did it change your vision?

I’m not sure if I would have decided to pursue art and design as my career without the experience I had working with Stephen, or at least it would have taken many more years for me to find out I could. It’s become a lot more common now to see people taking this path, but at the time I wasn’t seeing all that much of it. I did freelance work for him for a bit and was helping to build molds of large sculptural mirrors. He has such a clear vision for his work but really welcomed an exploratory process and there was such a playful energy he brought to discovering the final form. There was a willingness to try new things and potentially fail and start over and I had always been so precious about my creative work before that. I really admired how he bridged art and design, creating functional forms that could be shown in a gallery, which was something I had always dreamed about doing but didn’t know was possible.

You create inanimate sculptures inspiring yourself with movement. Can you tell us more about this part of your creative inspiration?

I have always been mainly interested in two things; the way things move, down to the smallest of things, and how we take up space, how space informs our behavior. There are so many ways that I have accumulated information from these interests in my life, but the one that really sits at the basin of everything is my ten-year participation — until I was 18 — in a dance company called Young Dance Collective.

We were formed post 9/11 as seven eight-year-olds with my best friend’s mom at the helm, who is the current creative director of Bill T Jones Company. We were all grappling with grief from that as well as from more personal experiences and were learning how to translate our thoughts and emotions into eight and 16 count dance phrases. To explain, I remember we all spread out across the room and had to write down something we felt shame around and put it in an envelope that had one word written across it to describe the feelings in the contents of the letter. We then had to make a dance sequence that represented that word and the contents of the letter. We met once a week and created all of our own movement and would have full-length shows every year. So, a preoccupation with shape, movement, form, gesture as a way to say something more — these are things that were embedded in me as a way to communicate.

It seems that a lot of your inspiration comes from looking at how shape manipulates natural light. Do you test your sculptures with light before creating the lamps, or do you go with your instinct first?

It’s very instinctual and also at this point, from experience. Like I’ve said my focus is already fully on how things move, and the way light interacts with objects in space is intrinsic to that. I also know how to create depth and manipulate the forms to create more shadow or catch light in a certain way. I like to work in a space where sunlight casts through so I can see how light is interacting with the work as I’m building.

What is your creative process like?

My process has a lot of different forms to it. I’m not so ritualistic with how I approach my creative process. I try to let it be a bit freer. Sometimes I come to the worktable with just a vague structure or an intended use in my mind and see what happens, sometimes I create directly from a sketch. When I do the former, I usually end up flipping the piece sideways or upside down midway and it’s like completing a puzzle, so it’s very nonlinear. My sketches come either from forms I’ve seen in my dreams, — I know that sounds like a load of crap but it’s true — that I scribbled down when I woke up, or an image of a zoomed in form I’ve seen like a table’s foot. And I riff on until I decide it needs to be created, or sometimes I make very gestural improvised drawings and then work the shape a lot until it feels right to me.

Your art is primarily made with clay — is there a particular reason you like to create with this medium? What other mediums do you love to create with?

Clay is primal, tactile. It really has life within it. It doesn’t give in to your every whim, which is very humbling and sometimes frustrating. But that allows you to really have a relationship with the medium, to listen to it and sometimes give in to what it wants. I also sometimes feel like a masochist working with clay because you have to give up so much control to the process. Sometimes things crack, or the glaze you always use somehow comes out looking horrible, and you just have to take it in stride.

Can you take us through a typical workday as a sculptor?

The pandemic has really offset any rituals I used to have. I also just moved to LA after living in New York for my entire life, so I’m learning how to exist in a whole new landscape and trying to create routine. If I can, I try to write or sketch first thing in the morning while having a cup of tea, but lately I’ve been picking up my phone first thing and I’m trying to quit that habit. I then spend all day in the studio, either filling orders or troubleshooting new forms, or working on glaze recipes. If I can, I’ve been going on a hike in the late afternoon and then headed home to do admin work which is

the less glamorous side of being an artist. People forget you also are running a business.

What does the future hold for Kassandra Thatcher?

I’m working on a few exciting projects and collaborations this year with new forms and shades. I’ve also finally gotten comfortable saying that I’m a lighting designer, so I’m workshopping other lighting elements like sconces, floor lamps, and pendants to offer. With how uncertain our world is these days, I’m just trying to focus on the work, and less on where I myself will be in a year or two from now. ■